Steve McQueen owned an extraordinary array of vehicles including a 1931 Pitcairn PA-8 biplane, a Ferrari 250 GT Lusso, a Jaguar XKSS, a Ford GT40 and a number of motorcycles – including the 1934 Indian Sport Scout you see here.

Although

he’s perhaps more famous for his association with Triumph and

Husqvarna, McQueen’s love of American motorcycles was never in doubt.

His first bike was a Harley-Davidson that was so oily and smoky that it

cost him the affection of the girl he had been dating, he also owned a

number of Indians including an old custom chopper, a Chief and of

course, a Sport Scout.

In some respects, the Indian Sport Scout

was a return to the roots of the Scout model line. The first two

generations of the model had been very popular and favoured for their

ability on race tracks, at hill climbs and in endurance events.

In

1932 Indian introduced the third generation Scout, it had been

developed with cost cutting in mind – and as is often the case when the

bean counters get involved, it resulted in a lot of disappointment. The

plan was to develop a single frame design and then use it as the base of

the Scout, the Chief, and the Four. The issue was that the frame was

heavy and cumbersome. This was a major drawback for a nimble, sporting

motorcycle like the Scout.

In some respects, the Indian Sport Scout

was a return to the roots of the Scout model line. The first two

generations of the model had been very popular and favoured for their

ability on race tracks, at hill climbs and in endurance events.

In

1932 Indian introduced the third generation Scout, it had been

developed with cost cutting in mind – and as is often the case when the

bean counters get involved, it resulted in a lot of disappointment. The

plan was to develop a single frame design and then use it as the base of

the Scout, the Chief, and the Four. The issue was that the frame was

heavy and cumbersome. This was a major drawback for a nimble, sporting

motorcycle like the Scout.

The public reaction to the new Scout

was almost entirely unfavourable and Indian set about trying to rectify

the situation as quickly as possible. Two years later they released the

new Sport Scout, it had a lighter frame, girder forks, improved

carburation and alloy cylinder heads – it addressed the concerns that

the pubic had raised with the third generation model and it returned the

Scout to its winning ways on the race tracks of North America. A

modified Indian Sport Scout would go on to win the first Daytona 200 in

1937, as well as hundreds of less famous races across the continent.

The

history of the 1934 Sport Scout wouldn’t have been lost on McQueen, he

was an avid motorcycle racer who funded his early acting career by

winning local races and living on the prize purses. This Indian was sold

from his collection in 2006 to a buyer in London who rode it sparingly

and displayed it in his office. It’s now being offered for sale with an

estimated value of between £55,000 and £65,000, if you’d like to read

more or register to bid you can click here.

The public reaction to the new Scout

was almost entirely unfavourable and Indian set about trying to rectify

the situation as quickly as possible. Two years later they released the

new Sport Scout, it had a lighter frame, girder forks, improved

carburation and alloy cylinder heads – it addressed the concerns that

the pubic had raised with the third generation model and it returned the

Scout to its winning ways on the race tracks of North America. A

modified Indian Sport Scout would go on to win the first Daytona 200 in

1937, as well as hundreds of less famous races across the continent.

The

history of the 1934 Sport Scout wouldn’t have been lost on McQueen, he

was an avid motorcycle racer who funded his early acting career by

winning local races and living on the prize purses. This Indian was sold

from his collection in 2006 to a buyer in London who rode it sparingly

and displayed it in his office. It’s now being offered for sale with an

estimated value of between £55,000 and £65,000, if you’d like to read

more or register to bid you can click here.

The Indian Chieftain is a big motorcycle, designed to soak up the miles

on the smooth highways of ‘Murica. The star of the show is the new Thunder Stroke engine, a mighty 111 cubic inch (1811cc) monster pumping out 119 ft-lbs of torque.

It’s a remarkably good-looking motor, and it caught the eye of Roland Sands,

the man who can do no wrong when it comes to creating genre-bending

customs. Sands has now tapped into Indian’s rich motorsport heritage,

and slotted the Thunder Stroke into a vintage-style,

boardtracker-inspired build: the Indian Track Chief.

There’s so much detail on this bike, it’s hard to know where to start.

“The inspiration came from a drag bike rendering that Sylvain from

Holographic Hammer sent to me,” says Sands. “I ended up tweaking it into

a boardtracker, adding the single sided element and all the detailing.

But we retained the spirit of the tank shape, girder fork and frame.”

That single-side rigid frame is a masterpiece, hugging the engine

just-so. It’s hand-fabricated from 4130 chromoly steel, finished in

black by Olympic Powdercoating.

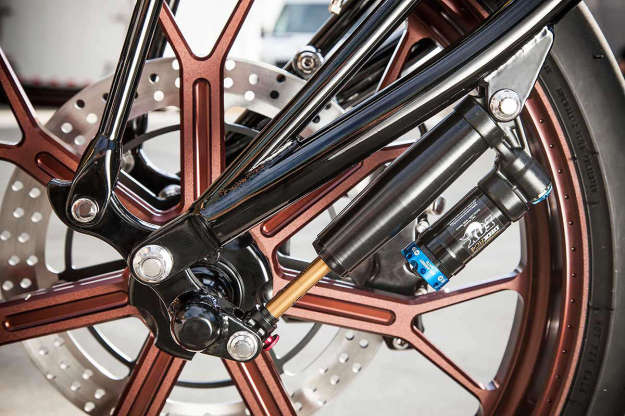

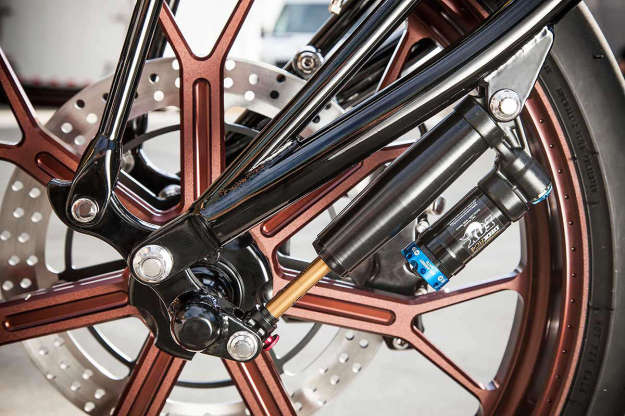

The frame is a perfect match for the black Paughco Leaf Spring Fork

assembly, a fascinating contraption designed for customizers who want a

vintage look with high-quality, modern construction. Tucked down low on

the left side of the fork, near the axle, is a Fox DHX mountain bike

shock—a component popular with riders on the World Cup downhill series.

“It controls the motion of the front end, and works really well,”

reports Sands’ project manager Cameron Brewer. “The compression and

rebound dampening of the shock is a perfect match to the rate of the

leaf spring.”

Sands: “Considering it was a rigid with a leaf fork, I had nightmares

about how it was going to handle. Function wise, it couldn’t have

turned out better. I rode the Track Chief all over Sturgis and in the

twisties, and was really happy with it.”

Sitting above the frame is a hand-fabricated titanium tank; hidden

below the frame is an aluminum belly pan. The internals of the Indian

Chieftain engine are stock, but there’s a Roland Sands Design Blunt air

cleaner, a high-flow, low-profile fitment that doesn’t get in the way of

your leg.

The titanium pipes of the custom 2-into-2 exhaust system follow the

lines of the V-twin snugly, and terminate in RSD Slant mufflers. “For

this bike, reliability was a top concern,” says Roland Sands. “So we

retained stockish elements so it would start every time. The wiring loom

was a big problem, but we had some underground help from Indian to

strip it down to the essentials.”

There’s a see-through RSD Clarity cam cover and a matching outer primary

cover too—revealing a custom clutch pressure plate from Barnett.

“We told Barnett we were making a one-off primary cover and wanted some

high-end billet clutch internals to show off. These are not production

parts for either of us, but may be down the road,” says Brewer.

Track Chief sports a serious turn of speed on the road: it’s

considerably lighter than the 827 lb. Chieftain that donated its engine.

“We haven’t weighed the bike,” says Brewer. “But two of us did pick the

Indian up by the wheels—if that’s any gauge of the actual weight, we’d

guess it’s in the 400-500 lb. range.” Sands himself adds: “The pile of

removed parts is massive!”

The handlebars are welded to the upper triple: allowing Sands to make

very narrow bars, and eliminating the use of risers. (“They are

basically clip-ons—without relying on a pinch bolt.”) RSD Traction Grips

with a custom bronze anodized finish add to the vintage look.

As we all know, wheels are critical to the boardtracker look. And

here we’ve got 21” x 3.5” lightweight RSD Del Mar rims—with the same

bronze finish as the grips. They’re shod with Dunlop Elite 3 tires,

which are conveniently available in a 120/70-21 size for custom builds.

Stopping power comes from Performance Machine calipers and Brembo cylinders, and the rear sprocket and drive unit come from Gregg’s Customs.

Paint is low-key: a classic Indian red and black combo, applied by Hot

Dog Pinstriping, with gold leaf for the oversized logo on the raw metal

tank.

It’s not the kind of machine that will find its way back into

Indian’s catalog any time soon. But the burgeoning cool factor of

America’s oldest motorcycle brand just stepped up a notch—or three.

Roland Sands Design | Indian Motorcycle

Image below courtesy of Barry Hathaway.

The story appeared first in http://www.bikeexif.com/

With all eyes on Indian Motorcycle’s relaunch of the iconic Scout, it’s refreshing to see vintage examples vying for attention too. And this eye-catching 1949 Scout from Analog Motorcycles should have no trouble stealing a little limelight.

Analog’s Tony Prust stumbled upon the bike while chasing up another

lead. “A friend and I headed north to take a look at a Kawasaki W1,” he

explains. “While we’re there, we see a rolling chassis and a pile of

parts sitting on a bench in the corner. It was a 1949 Indian Scout with a

title that the owner had had for seventeen years.”

“He’d several projects going in his shop, and his friends gave him a

hard time about the Indian, saying that he was never going to finish

it.” After some negotiation, the owner finally relented. “It was pretty

far beyond restoration quality,” says Tony, “but had most of the

ingredients needed to build a motorcycle.”

The 1949 Scout was built around a 440cc vertical twin in a

plunger-style frame. According to Tony, many experts consider it to be

the bike that put Indian out of business. “They bought the design from a

European company and put it into production without much testing.”

(Bonhams has a 1949 Super Scout listed on their site, with a great

little history lesson.)

Given the plunger rear end, a bobber-style build seemed obvious. But

Tony had higher aspirations for the little Scout, and decided to create a

’60s and ’70s-era race replica. The first step was getting the motor

into a better chassis, so Tony called up Randy and Karsten at Frame

Crafters in Union, Illinois. “After chatting with them for a bit and

realizing how obscure the engine was, we decided to modify a Track

Master-style frame that they had in-house. This was the go-to chassis

for many racers back in the ’60s & ’70s.”

It took some shoehorning, but Frame Masters managed to squeeze in the

Scout’s engine and transmission. Analog then installed a set of vintage

Betor forks, matched to modern Gazi shocks, and a new wheel set: TZ750

hubs laced to 18” aluminum rims.

With the rolling chassis sorted, the engine was next on the list. Frame

Crafters recommended Bill Bailey of ZyZX Vintage Motorcycles: an

ex-racer who had piloted old Indian Scouts and Warriors. “Bill had done a

lot of racing and testing, and discovered the engine’s weaknesses and

ways to improve it.”

During the rebuild the engine was punched out to 500cc with a

hand-cut billet cylinder. The electrical system was converted to 12-volt

with an electronic ignition, and the oil cooling system was redesigned

and hooked up to a new oil tank.

Next up was the Scout’s bodywork. Tony shaped bucks of the tank and tail

sections out of Styrofoam, and sent them off Pavletic Metal Shaping to

hand-build aluminum versions. Pavletic also handled the aluminum

fairing—based on a wire frame template that Tony mocked up.

Turning to the finer details, Analog fabricated a new exhaust system,

terminating in Cone Engineering Stubby mufflers. Tony also fitted

Tarozzi rear-sets, with levers that fold out of the way of the

kickstart. (Tony lists the redesigned kickstart lever as one of the

trickiest parts of the entire project). All the plumbing was replaced by

brass lines and braided stainless tubing. The speedo is a one-off from

Seattle Speedometer, and Free Form Designs handled the speedo bracket,

rear sprocket and oil manifold.

Much consideration went into the final finishes: “The plan was to do raw

aluminum, but after seeing a lot of motorcycles coming out in recent

months with the same look, I opted to give it more color.” Analog

“Scotch-Brited” all of the aluminum bodywork before clear-coating it.

Regular Analog collaborators were called in: Kiel of Crown Auto Body for

paint, Brando for pin striping and gold leaf, and Art Rodriguez of Rods

Designs for the seat’s leatherwork.

Despite the race-inspired looks, the Scout is fully street legal

thanks to LED head and taillights. “To keep it in race trim I had Mike

Ardito form brass covers to go over the headlight and taillight. While

he had the bike, he also whipped up the front fender.”

With parts from every corner of the globe, Analog decided to call the

bike the Continental Scout. “The bike was designed entirely by Analog

Motorcycles,” says Tony, “but it was my vision to go beyond some of my

fabrication abilities—so I called on skilled professionals to achieve

the final product. It is without a doubt the most beautiful motorcycle I

have created so far and I am extremely proud of it.”

And so you should be, Tony. Now please get cracking on that Kawasaki W1.

Photography by Whiplash Racing Media. To see more of Tony Prust’s work, visit the Analog Motorcycles website.

Full Build Sheet

Track Master style frame made by Frame Crafters

All aluminum tank, seat and fairing designed by Analog and formed by Pavletic Metal Shaping

Brass light covers and fender formed by Mike Ardito

Polishing by Mike’s Polishing, Rodsmith, and Analog

Engine built by Bill Bailey of ZyZX Vintage Motorcycles

Engine has hand-cut billet cyclinder, 12 volt conversion and Dyna III electronic ignition.

Carburetor: Amal 928

Exhaust custom made by Analog with parts and stubby mufflers from Cone Engineering

Custom-made oil tank with internal plumbing made by Chassis Services

All plumbing designed and made by Analog

Paint and clear coat by Kiel of Crown Autobody

Gold leaf and pin-striping by Brando

Seat by Rod’s Designs

Magura controls

Speedometer designed and rebuilt by Seattle Speedometer

Tarrozi rear sets

Betor Forks and triples

TZ750 hubs with custom detailing by Analog

Spokes and rims made by Buchanan’s

Speedo mount, rear sprocket and oil manifold machined by Free Form Design

Gas cap by Crime Scene Choppers

Piaa LED headlights

Radiantz puck LED taillight frenched into seat hump

All custom electrical – battery and fuse block under seat hump

Custom made bar switch by Analog

Modified GSXR windscreen

Maund Speed Equipment velocity stack

Avon Roadrider tires

All custom made cables by Ed Zender at Morrie’s Place

Extremely strange and difficult to design custom kick starter lever (version 5) by Analog

Top oiler lines made by HEL brake lines

The post Indian Scout by Analog Motorcycles appeared first on Bike EXIF.

When Clayton Schaefer from Street Spirit Cycles received a phone call from a customer asking whether he would “café my

Indian?” his first thought was “there’s no way, it would be a

sacrilege!”. He just couldn’t imagine taking the sawzall to a piece of

motorcycle history. “But as we went back and forth I learned that we

weren’t just talking about any Indian”, says Clayton. ”We were talking

about the Indian that bankrupted the company: the slow, awkward, 213cc

cousin of the beloved big twins”. You see, the Arrow 149 was one of the

last bikes to roll out of the original Indian factory floor before they

went out of business. It seems the development costs and teething

problems of this little motorcycle may have actually been the final nail

in the coffin. So with that in mind Clayton took on the job – but

decided to leave the sawzall alone.

When Clayton Schaefer from Street Spirit Cycles received a phone call from a customer asking whether he would “café my

Indian?” his first thought was “there’s no way, it would be a

sacrilege!”. He just couldn’t imagine taking the sawzall to a piece of

motorcycle history. “But as we went back and forth I learned that we

weren’t just talking about any Indian”, says Clayton. ”We were talking

about the Indian that bankrupted the company: the slow, awkward, 213cc

cousin of the beloved big twins”. You see, the Arrow 149 was one of the

last bikes to roll out of the original Indian factory floor before they

went out of business. It seems the development costs and teething

problems of this little motorcycle may have actually been the final nail

in the coffin. So with that in mind Clayton took on the job – but

decided to leave the sawzall alone.

After Clayton took a good look at the bike he determined that it had

been modified and “restored” at least once already, and that it’s value

as a collector’s piece was probably pretty low as a result. “To be on

the safe side, we agreed on a build that would preserve all the

components that came on the bike, leaving the frame intact and

unmodified. This created some interesting challenges, because normally I

wouldn’t think twice about welding a bracket here or cutting off an

offending tab there in the course of setting up a bike.”

After Clayton took a good look at the bike he determined that it had

been modified and “restored” at least once already, and that it’s value

as a collector’s piece was probably pretty low as a result. “To be on

the safe side, we agreed on a build that would preserve all the

components that came on the bike, leaving the frame intact and

unmodified. This created some interesting challenges, because normally I

wouldn’t think twice about welding a bracket here or cutting off an

offending tab there in the course of setting up a bike.”

“By far the most complicated piece was the mounting bracket for the

rearsets, which had to bolt to the only available hole in the frame in

the tiny space in front of the rear tire below the battery box, clearing

the chain, centre stand, exhaust, and transmission case, and leaving

enough room for proper operation of the shifter and brakes. The way the

bracket is shaped, rider weight goes down onto the side rails of the

frame rather than depending on the single fastener through the tube.”

“By far the most complicated piece was the mounting bracket for the

rearsets, which had to bolt to the only available hole in the frame in

the tiny space in front of the rear tire below the battery box, clearing

the chain, centre stand, exhaust, and transmission case, and leaving

enough room for proper operation of the shifter and brakes. The way the

bracket is shaped, rider weight goes down onto the side rails of the

frame rather than depending on the single fastener through the tube.”

“The actual rearsets consist of a mix of handmade parts and pieces

scavenged from other builds, like the shifter linkage ball joints from a

GS450 and the passenger peg mounts from a Ninja 250.

On the hand controls, the original Indian had a pretty funky setup –

big high cruiser bars that didn’t match the diameter of any available on

the market today. We ended up going to more common 7/8″ standard, but

to preserve the vintage look and feel of the bike, we used handmade

solid brass risers and levers. The ‘mustache handlebar’ creates a nice

low riding position and makes the bike look more like plausible period

mod.”

“The actual rearsets consist of a mix of handmade parts and pieces

scavenged from other builds, like the shifter linkage ball joints from a

GS450 and the passenger peg mounts from a Ninja 250.

On the hand controls, the original Indian had a pretty funky setup –

big high cruiser bars that didn’t match the diameter of any available on

the market today. We ended up going to more common 7/8″ standard, but

to preserve the vintage look and feel of the bike, we used handmade

solid brass risers and levers. The ‘mustache handlebar’ creates a nice

low riding position and makes the bike look more like plausible period

mod.”

“The carburetor is a Dell’Orto remote float unit with a velocity

stack and gasses exit through an open header. It has a points and coil

setup that replaced notoriously unreliable ignition on the original

bikes, and it’s been converted to a solid state voltage regulator and a

sealed lead acid battery. Headlight is original with new switchgear, and

the tail light is from the Harley aftermarket.”

“The carburetor is a Dell’Orto remote float unit with a velocity

stack and gasses exit through an open header. It has a points and coil

setup that replaced notoriously unreliable ignition on the original

bikes, and it’s been converted to a solid state voltage regulator and a

sealed lead acid battery. Headlight is original with new switchgear, and

the tail light is from the Harley aftermarket.”

“Side covers have been resealed, which improved the oil leak

situation considerably, but I’m pretty sure these bikes leaked oil when

they were brand new so there’s only so much you can do.

Other than that, we just cleaned her up and removed as much

unnecessary junk as possible to get the weight down and improve

handling. I know at least one person who commutes daily on a ’40s

Indian, but it’s probably best to save it for those sunny afternoons

when you have nowhere in particular to be.”

“Side covers have been resealed, which improved the oil leak

situation considerably, but I’m pretty sure these bikes leaked oil when

they were brand new so there’s only so much you can do.

Other than that, we just cleaned her up and removed as much

unnecessary junk as possible to get the weight down and improve

handling. I know at least one person who commutes daily on a ’40s

Indian, but it’s probably best to save it for those sunny afternoons

when you have nowhere in particular to be.”

First appeared in www.pipeburn.com

In some respects, the Indian Sport Scout

was a return to the roots of the Scout model line. The first two

generations of the model had been very popular and favoured for their

ability on race tracks, at hill climbs and in endurance events.

In some respects, the Indian Sport Scout

was a return to the roots of the Scout model line. The first two

generations of the model had been very popular and favoured for their

ability on race tracks, at hill climbs and in endurance events. The public reaction to the new Scout

was almost entirely unfavourable and Indian set about trying to rectify

the situation as quickly as possible. Two years later they released the

new Sport Scout, it had a lighter frame, girder forks, improved

carburation and alloy cylinder heads – it addressed the concerns that

the pubic had raised with the third generation model and it returned the

Scout to its winning ways on the race tracks of North America. A

modified Indian Sport Scout would go on to win the first Daytona 200 in

1937, as well as hundreds of less famous races across the continent.

The public reaction to the new Scout

was almost entirely unfavourable and Indian set about trying to rectify

the situation as quickly as possible. Two years later they released the

new Sport Scout, it had a lighter frame, girder forks, improved

carburation and alloy cylinder heads – it addressed the concerns that

the pubic had raised with the third generation model and it returned the

Scout to its winning ways on the race tracks of North America. A

modified Indian Sport Scout would go on to win the first Daytona 200 in

1937, as well as hundreds of less famous races across the continent.